We often hear about the vaginal flora or the vaginal microbiota. But what are they really? What is their function and how to take care of them? We answer you in this very complete article.

What is in my vagina?

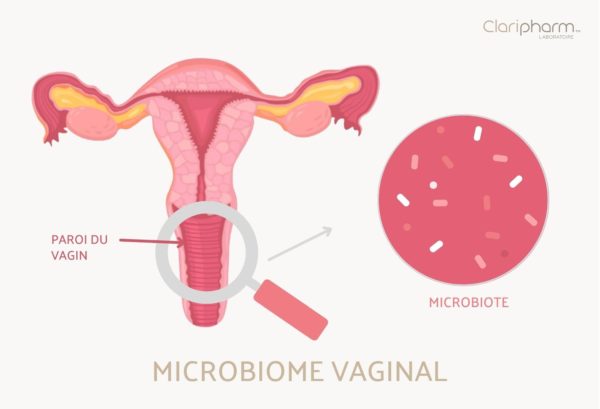

Our vagina is composed of a wall covered with a mucous membrane lubricated by cervico-vaginal fluid. Together they form a formidable barrier against foreign invading organisms responsible forinfections, dryness and/or intimate irritation(Amabebe & Anumba, 2018).

Before detailing what is inside our vagina, we will first define the important terms:

What is the microbiome?

It corresponds to all the micro-organisms present in the vagina as well as all the environment which contains them.

What is the microbiota?

The microbiota is the set of microorganisms that inhabitthe microbiome.

What microorganisms make up the vaginal microbiota?

A “healthy” microbiota is generally dominated by Lactobacilli: “good” bacteria producing lactic acid.

Thus, the main strains are:

- Lactobacillus crispatus,

- Lactobacillus gasseri,

- Lactobacillus iners,

- Lactobacillus jensenii (Tachedjian et al., 2017).

In addition to these Lactobacilli, the microbiota is also composed of a polymicrobial mix that is beneficial to our health (Smith & Ravel, 2017).

The vaginal microbiota is not the only important attribute to consider in the functional definition of the vagina. The health of the vagina also depends on its structure and changes over time, the influence of ethnicityand the genetic disposition of the woman (Buchta, 2018).

What are the characteristics of a “healthy” vaginal microbiota?

The main characteristics of women with vaginal microbiota and microbiomes associated with a healthy state, are:

- a vaginal pH of 4.5

- A beneficial metabolite profile: presence of lactic acid and alpha-hydroxy acid (Tachedjianet al., 2017).

What is the role of the vaginal flora?

Some of these microorganisms, such as Lactobacilli, strengthen the defense against invasion and colonization by harmful bacteria.

Thisacidic environmentwould be highlyprotective againstinfectionsor colonization of the vagina by these pathogens and microbes.

The vaginal microbiotaprovides aneffective first-line defense against invading pathogens, including bacterial vaginosis, bacteria associated with vaginitis, viruses and fungi .

How do Lactobacilli work to protect the vagina?

Lactobacilli have the role of making the vagina acidic. These microorganisms are able to use glycogen to produce lactic acid.

Lactobacilli, fermentative bacteria as well as vaginal epithelial cells (composing the vaginal wall), produce lactic acid by fermentation of glucose and are responsible forthe acidification of the vaginal environment.

The vagina: a particular structure worthy of a castle

- The vaginal microbiomehelps protect the vagina by producing lactic acid to make the environment acidic to fight against bad bacteria.

- The vaginal mucosa plays an important role as a physical barrier to separate the vaginal wall from microbes (Smith & Ravel, 2017).

- The female reproductive tract is considered a formidable chemical and physical barrier to invading organisms, in part because of the structure of its walls and the presence of cervico-vaginal fluid.

- Cervico-vaginal fluid acts as an effective lubricant, facilitates the entrapment of bad organisms, and acts as an acidic medium in which an arsenal of antimicrobial molecules (antibodies, defensins, etc.) are found (Aldunate et al., 2015).

Changes in the microbiota during the life of the vagina

The composition of the vaginal microbiota changes throughout a woman’s reproductive life, that is, from birth through puberty, pregnancy, and menopause (Smith & Ravel, 2017).

The composition of the vaginal microbiota/microbiome undergoes changes corresponding to hormonal fluctuations (Amabebe & Anumba, 2018).

Origin of the microbiota

The infant’s microbiota is populated with maternal bacteria at birth, from the vagina in the case of natural childbirth or from the skin in the case of cesarean delivery.

At birth, the bacterial communities on the infant’s skin, oral cavity, nasopharynx, and gut are largely undifferentiated, suggesting that the composition of a female infant’s vaginal microbiota would be populated with communities similar to those of her mother (Moosaet al., 2020).

The microbiota during childhood

The early childhood vaginal microbiota includes a variety of microorganisms, such as diphtheroids, staphylococci and E. coli. Glycogen is significantly lower than in adulthood (Amabebe & Anumba, 2018; Muhleisen & Herbst-Kralovetz, 2016).

The microbiota in women of childbearing age

The vaginal microbiota in women of childbearing age is generally dominated by Lactobacillus crispatus,Lactobacillus gasseri,Lactobacillus iners and Lactobacillus jensenii, most of which produce large quantities of lactic acid (Tachedjian et al., 2017).

Normal acidic vaginal pH in women of reproductive age is determined by estrogen, glycogen, and Lactobacilli (Amabebe & Anumba, 2018).

The microbiota at puberty or during pregnancy

During puberty, as during pregnancy, increased estrogen levels promote maturation, proliferation of cells in the vaginal wall and accumulation of glycogen.

The glycogen is then metabolized into lactic acid by the Lactobacilli. This creates an acidic environment (pH, 3.5-4.5) favorable to the growth of Lactobacilli at the expense of other bacteria.

The microbiota in menopausal women

The vaginal microbiota is particularly important for postmenopausal women and can have a profound effect on vulvovaginal atrophy, vaginal dryness, sexual health, and overall quality of life (Muhleisen & Herbst-Kralovetz, 2016).

Menopausal women often experience a loss of Lactobacilli associated with the decrease in estrogen (controlling the proliferation of cells that make up the vaginal wall), maturation, and accumulation of glycogen (Muhleisen & Herbst-Kralovetz, 2016).

Taking hormone replacement therapy has a direct effect on the dominance of Lactobacilli in the microbiota and may resolve vaginal symptoms (Muhleisen & Herbst-Kralovetz, 2016).

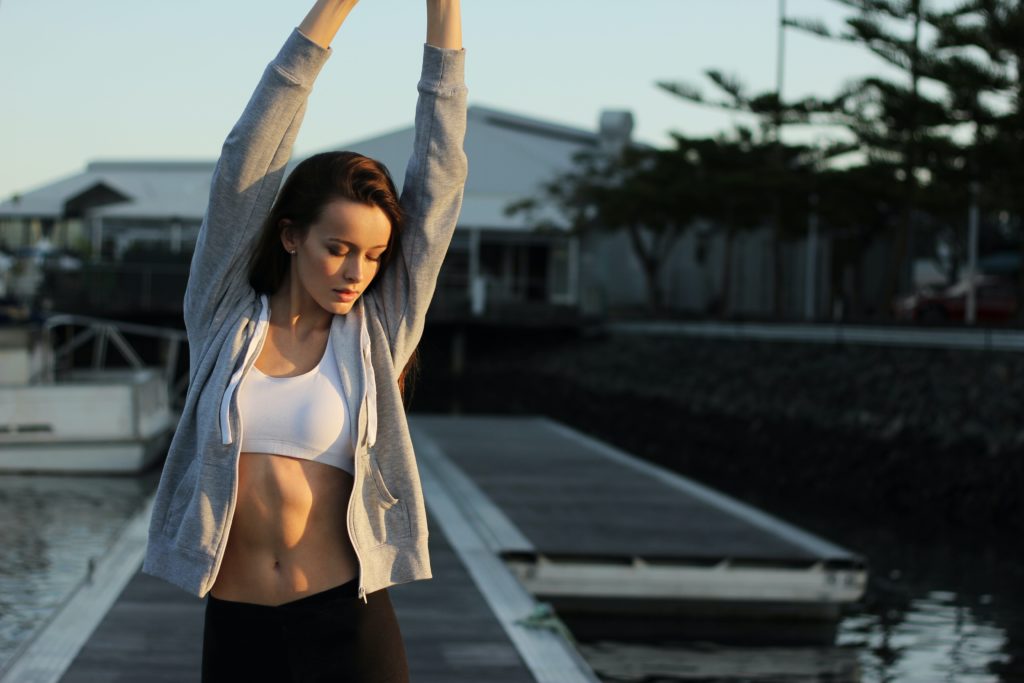

The microbiota during menstruation

Vaginal microbial diversity increases and the number of Lactobacilli decreases duringmenstruation (Moosaet al., 2020). The risk of infection is increased during this period. Hence the importance of using a appropriate intimate shower geland sanitary protection without toxic compounds that could irritate, damage or dry out the vulva.

Dysregulation of the vaginal flora and appearance of pathologies

Ideal pH to protect the vagina

It has been shown that the vaginal microbiotabeing composed of Lactobacilli, leads to a low pHof 3.5 to 4.5, which protects women from vaginal dysbiosis, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) andadverse pregnancy outcomes (Vaneechoutte, 2017).

Disorder and vaginal infections

Sometimes the concentrations of Lactobacilli in the vaginal microbiota are altered. This produces a imbalancewith a low quantity of Lactobacilli and an increase in pathogenic microorganisms.

This altered state can take the form of dysbiosis, usually characterized by the appearance of bacterial vaginosis.

Characteristics of the vaginal microbiome change

This condition is described for 3 main changes in the vaginal environment :

- a change in the composition of the vaginal microbiota including Lactobacilli,

- the production of deleterious compounds by the new bacterial microbiota;

- an increase in vaginal pH to over 4.5.

These are the conditions that favor the development of opportunistic microorganisms that behave as pathogens, whether they are located in the vagina or brought by the external environment.

Therefore, the vaginal flora in imbalance is moresusceptible to diseases, including the occurrence ofSTIs and obstetric and reproductive discomfort (Barrientos-Durán et al.,2020 ; Laue et al., 2018 ; Tachedjian et al., 2017).

4 habits that unbalance our vaginal flora

There are certain types of behaviors that can influence vaginal acidity levels, which can predispose to the overgrowth of bad bacteria.

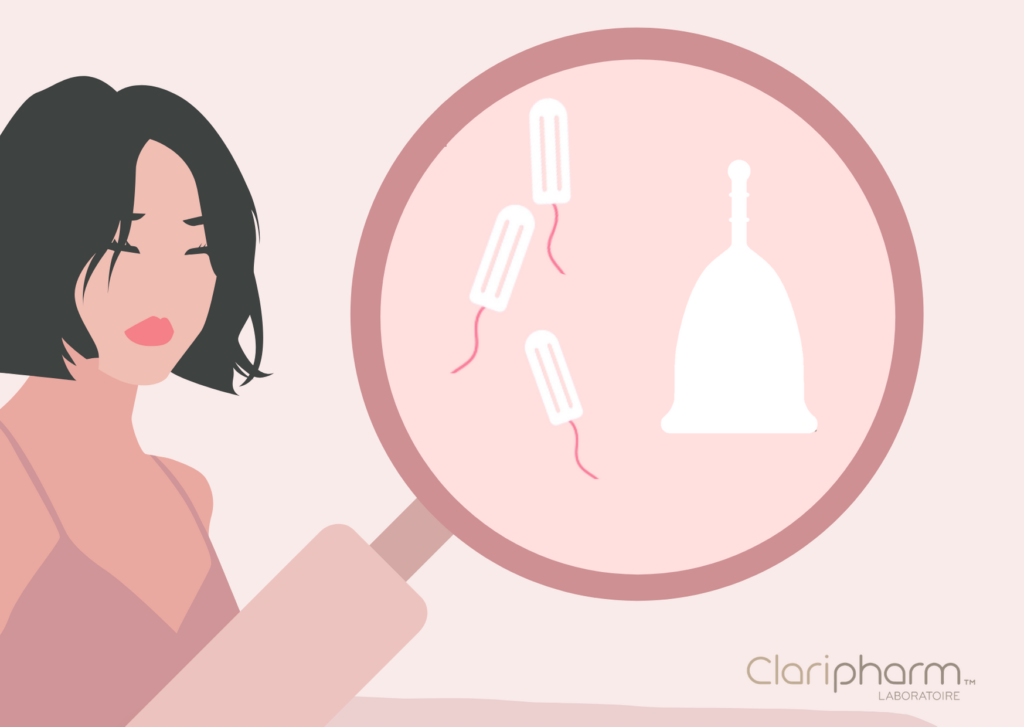

Be careful with the use of intimate products

The use of :

- unsuitable feminine hygiene products,

- poor quality tampons and sanitary napkins,

can alter the vaginal immune barrier,affecting its health.

In fact, a tampon has the effect of absorbing the flow and vaginal mucus, unlike the menstrual cup which collects the bloodthat flows naturallywithout interferingwith the vaginal flora.

What about douching?

Others, such asvaginal discharge, have long been associated with the acquisition ofvaginal bacteriosis. Thus, studies suggest that women who are accustomed to these practices have an increased risk of incident vaginal bacteriosis (Barrientos-Durán et al., 2020).

Menstruation and sexuality: changes in vaginal pH

It has also been reported that the alkalinity ofmenstruationor sperm temporarily neutralizes the vaginal pH and could have an impact on the vaginal microbiota. (Barrientos-Duránet al., 2020).

Beware of our lifestyle and our consumption

Also, the inappropriate or prolonged use ofantibioticsthat can penetrate the vaginal exudate, leading to an alteration of the ecosystem of the vagina.

The impact of smokingand dietary habits also affect the balance of the microbiota(Barrientos-Durá et al., 2020).

Are you wondering how to take care of your vaginal flora?

We tell you everything in the following article: “4 tips to balance your vaginal flora”

Bibliography:

Aldunate M, Srbinovski D, Hearps AC, Latham CF, Ramsland PA, Gugasyan R, Cone RA, Tachedjian G. Antimicrobial and immune modulatory effects of lactic acid and short chain fatty acids produced by vaginal microbiota associated with eubiosis and bacterial vaginosis. Front Physiol. 2015 Jun 2;6:164. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26082720/

Amabebe E, Anumba DOC. The Vaginal Microenvironment: The Physiologic Role of Lactobacilli. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018 Jun 13;5:181. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29951482/

Barrientos-Durán A, Fuentes-López A, de Salazar A, Plaza-Díaz J, García F. Reviewing the Composition of Vaginal Microbiota: Inclusion of Nutrition and Probiotic Factors in the Maintenance of Eubiosis. Nutrients. 2020 Feb 6;12(2):419. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32041107/

Buchta V. Vaginal microbiome. Ceska Gynekol. 2018 Winter;83(5):371-379. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30848142/

Laue C, Papazova E, Liesegang A, Pannenbeckers A, Arendarski P, Linnerth B, Domig KJ, Kneifel W, Petricevic L, Schrezenmeir J. Effect of a yoghurt drink containing Lactobacillus strains on bacterial vaginosis in women – a double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical pilot trial. Benef Microbes. 2018 Jan 29;9(1):35-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29065710/

Moosa Y, Kwon D, de Oliveira T, Wong EB. Determinants of Vaginal Microbiota Composition. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020 Sep 2;10:467. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32984081/

Muhleisen AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Menopause and the vaginal microbiome. Maturitas. 2016 Sep;91:42-50. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27451320/

Smith SB, Ravel J. The vaginal microbiota, host defence and reproductive physiology. J Physiol. 2017 Jan 15;595(2):451-463. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27373840/

Tachedjian G, Aldunate M, Bradshaw CS, Cone RA. The role of lactic acid production by probiotic Lactobacillus species in vaginal health. Res Microbiol. 2017 Nov-Dec;168(9-10):782-792. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28435139/

Vaneechoutte M. The human vaginal microbial community. Res Microbiol. 2017 Nov-Dec;168(9-10):811-825. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28851670/